In a previous post, I (outrageously) argued that Dett’s time at Harvard University was not spent in the way that current research presents it, namely, that he took coursework with Archibald Davison. In that post, I showed the courses that Archibald Davison taught on the (Harvard) record, which means that it probably happened that way because, hey, that’s how Harvard rolls.

I would like to present how Ann Key Simpson reports Dett’s Harvard year, because her reckoning lies at the heart of a crucial research issue for Dett (and likely others from this time period): sources collide and spawn most of the difficulties with which this blog grapples. To be clear, I am arguing that research sources themselves collide, and this should not be taken as meaning that the researchers who use these sources are actually at odds with one another. That is a big difference.

In her biography Follow Me, Simpson reports via “Information found in Hampton University Archives [p. 292n, p 594 note 35] that Dett’s teachers at Harvard aside from Dr Davison (who was not a Visiting Assistant Professor at Harvard but a regular member of the faculty) were a “Mr. Spalding” for counterpoint, composition (perhaps not in distinction to counterpoint), and appreciation; and a “Mr. Hill” for instrumentation. I do not know the exact nature of Simpson’s source for these courses, but her descriptions seem to match what is listed in the 1919-1920 catalog as if she were referring to it directly.

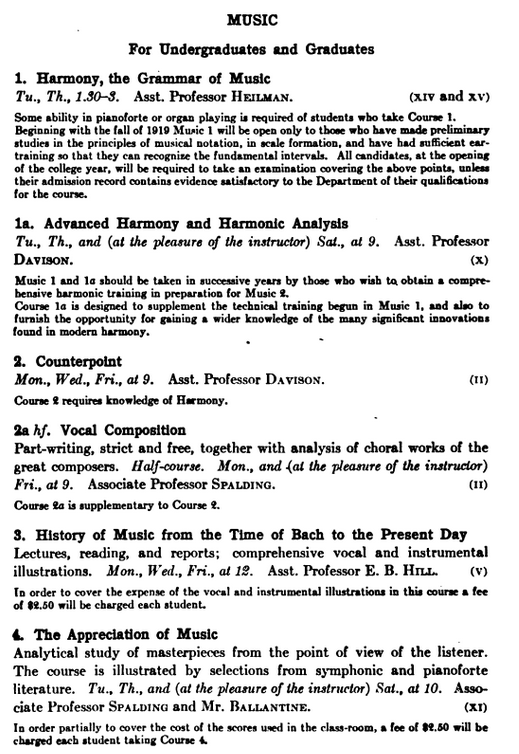

Among undergraduate core courses (the first of three graphics shown below) that Simpson provides are: Music 2a Vocal Composition (part-writing), Associate Professor Walter Raymond Spalding, AM (not a PhD); Music 3 History (Bach through present day), Assistant Professor Edward Burlingame Hill, AB (also not a PhD); and Music 4 The Appreciation of Music, Spalding and a “Mr Ballantine,” who is Edward Ballantine (no degrees), Instructor of Music. The sum total of undergraduate courses seems to match Simpson’s list almost exactly.

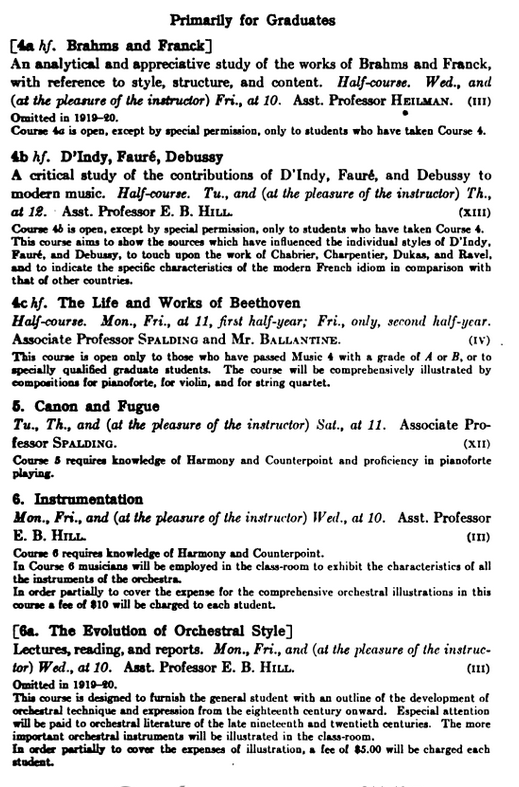

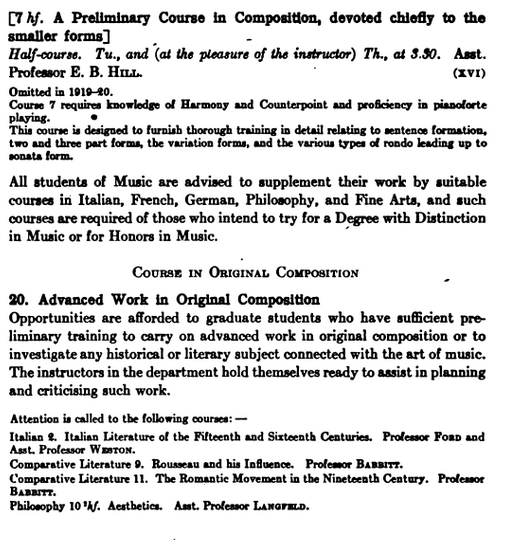

However, to make things problematic, the graduate-level courses on offer resemble the undergraduate course descriptions very closely: Music 4b D’Indy, Faure, Debussy, Hill; Music 4c Beethoven, Spalding and Ballantine; Music 5 Canon and Fugue, Spalding; Music 6a The Evolution of Orchestral Style, Hill; Music 20 Advanced Work in Original Composition [interdisciplinary courses with comparative-literature and foreign-language study, geared towards opera?], no faculty specified.

In sum, I am not willing to trust the course list attributed to Dett by Simpson for several reasons: 1) there is no way to tell in which courses Dett enrolled (or audited, which is a big difference); 2) there is no way to tell whether they were at the undergraduate (unlikely) or graduate level; and 3) Simpson reports that Dett wrote to Hampton Principal James E. Gregg (his boss) on 27 September 1919 that “required attendance to concerts was costly,” [p. 78] but none of the courses she lists required attendance to off-campus concerts. In sum, reason 3) is what makes me believe that Simpson’s description is based on a course listing, whether published by Harvard directly or recorded by some other and unspecified means, and not an official transcript. The fact that Simpson’s list also seems to be confined to undergraduate courses (reason #2) also makes me very, very suspicious, since they would have replicated his Oberlin coursework.

Further, she reports that Dett wrote to Gregg on 12 October 1919 saying that “he was enjoying extra courses other than the ones formerly scheduled. He had never seen a professor sitting cross-legged, smoking in class.” [p. 78] In the same letter, Dett also provides a detailed description of Pierre Monteux, then conductor of the Boston Symphony.

The only possible course for which off-campus concerts might have been required would be the graduate-level Music 4 series, which included Music 4 General Music Appreciation, Music 4a D’Indy, Fauré, and Debussy, and Music 4c The Life and Works of Beethoven for the 1919-1920 year. The description for Music 4c states that all musical examples would be limited to works for solo piano, solo violin, or string quartet, which precludes any Boston Symphony concerts. Music 4 states that a $2.50 fee will be charged to cover scores from the symphonic and pianoforte literature, but not that concert tickets would be required.

That leaves Music 4a D’Indy, Fauré and Debussy. This course bears the strongest connection to the BSO’s 1919-1920 season, in which Monteux was appointed and began to introduce new works of non-Germanic composers; this took place during a climate of anti-German sentiment due to the First World War. Not only were D’Indy, Debussy, and Ravel played throughout this season, but so were Liszt’s Les Préludes, the score for which Dett possessed (his copy is now in the Dett Collection of Eastman’s Sibley Music Library).

I would venture to propose that we approach other of Simpson’s Hampton sources with caution. She dutifully reports what she finds, but what the Hampton Archives hold must be corroborated by outside sources. I will elaborate more on why this corroboration is needed in other posts. I would go even further and assert that we need to corroborate all information we currently have about Dett.

Until then, we are back to the initial question left by my previous post on Arthur Foote: what did Dett do on his sabbatical that year? In my opinion, I think we can add “not take undergraduate courses with anyone” to our list, but we still cannot add anything definitive about the coursework element of his Harvard sabbatical at this point.